Happy Friday, everyone.

Last month I shared some of the story of Alice, my 4-year-old daughter, learning extraordinarily advanced literacy the Montessori way. Today I want to share an additional chapter of that story: an experiment that we conducted at home.

The experiment was performed in the vein of Montessori’s educational experiments. We (her parents) gave Alice a highly designed and enticing learning material, observed her using the material under conditions of freedom, and adjusted the material accordingly. The learning material was an iPad.

Specifically, it was an iPad set up to do three and only three things:

Take and view photos and videos

Type in the Notes app

Exchange text messages with a handful of specific people, including her (Guidepost-Montessori-enrolled) 4-year-old friend

We judged that these three activities were good enough—that they had sufficient developmental value—that it would be okay, indeed healthy, for her to choose to use the iPad for arbitrary amounts of unsupervised time. These affordances are each conducive to virtue: they are active, reality-oriented, and hone skills with broad, enduring benefits.1 We gave her the iPad, and then we stepped back and observed over days and weeks.2

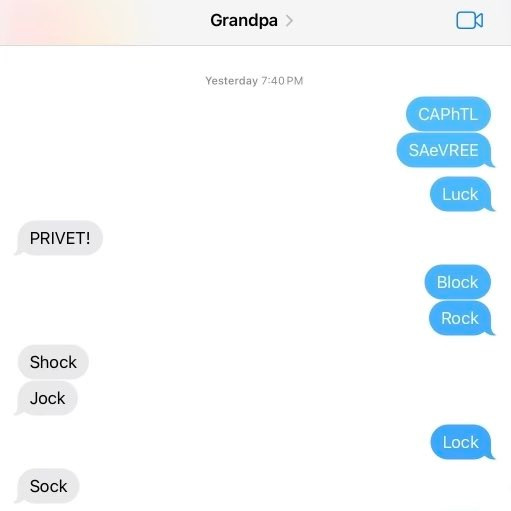

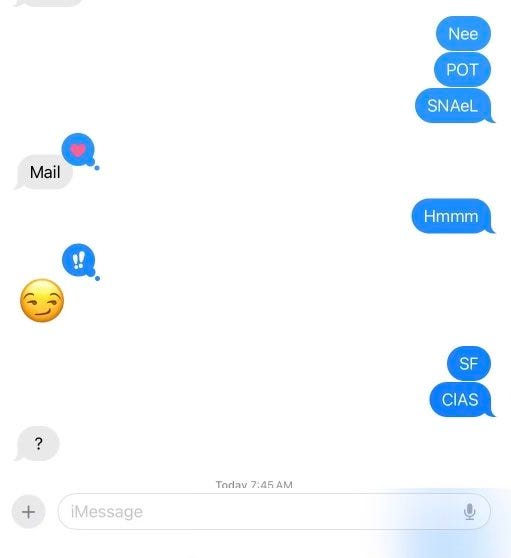

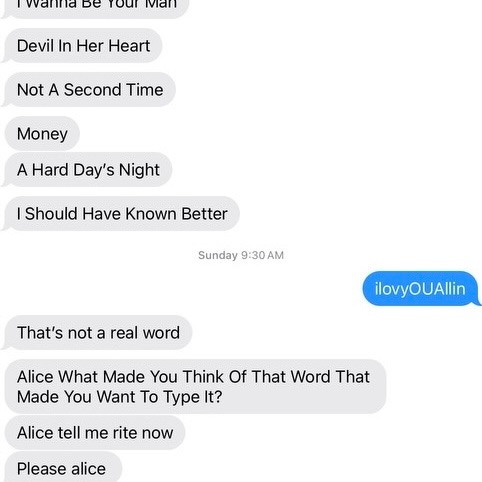

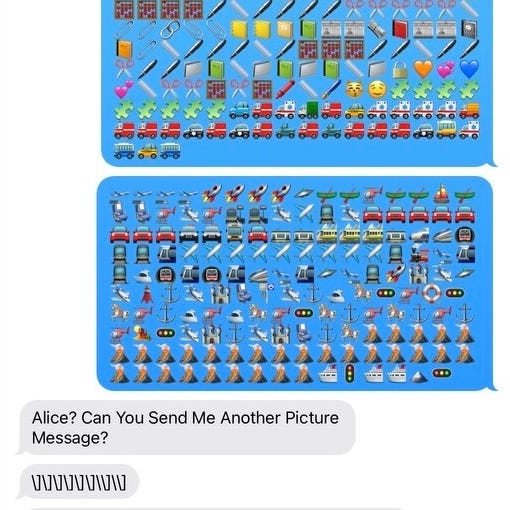

The big hit was text messages.

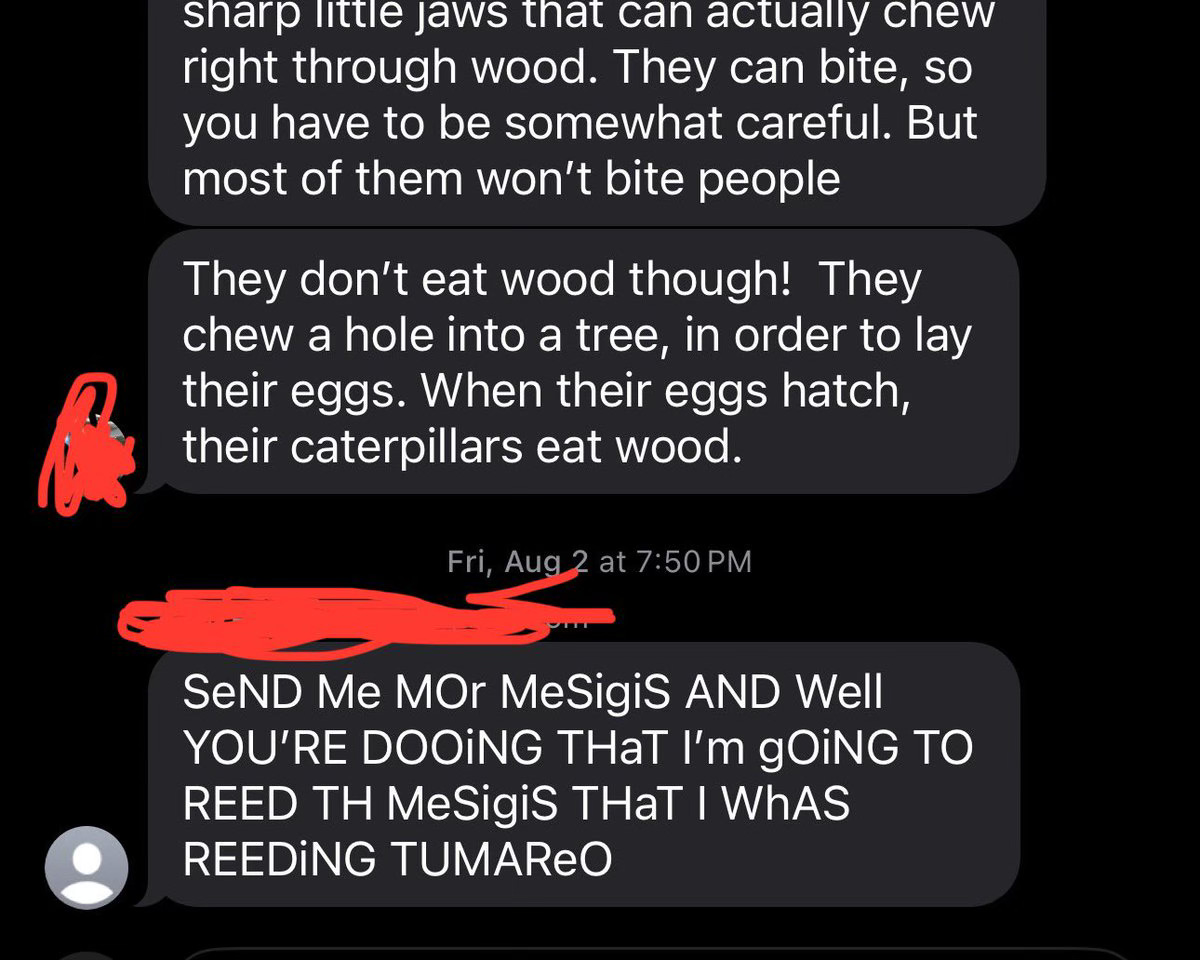

Alice would sit for long stretches, sometimes an hour or more, struggling to parse out a text message that she had received or, more commonly, patiently pecking out a message that she wanted to send.

Here’s the last part of an exchange she had with a family friend (and brilliant science educator) about a beetle that she found. Reading his messages and writing this response took her about half an hour:

All of this served as reading practice, and, more than anything, writing practice. It was writing practice with two spectacularly great features:

A movable alphabet. The software keyboard of the iPad isn’t perfect. (By the way, if someone wants to design an iOS keyboard that closely replicates the aesthetic of Montessori movable alphabet, that would be amazing.) But it’s quite good. It is, effectively, a sort of movable alphabet: it presents inscribing a letter as a pre-fabricated affordance, enabling a child to engage in the act of composition before they are capable of handwriting.

Real communication. Each text message was a real message to someone important to her. It was a way to actually express herself, in writing, to someone who she loves to talk to but who wasn’t present. It is in this respect superior to many classroom exercises, which are “mere” exercises, ends-in-themselves without purpose beyond expression and self-perfection. To be clear, these are good purposes! But it is enriching to add to them a communicative purpose.3

A huge portion of Alice’s out-of-school writing practice, during her sensitive period for writing, has taken place via text messages.

A child texting does not have especially positive connotations (which I’ll return to in a moment). But in fact text messages are pedagogically perfect for this specific moment, the “writing before reading” phase, when a child is not yet a fluent reader but is capable of writing. 4-year-olds are, in effect, in a sensitive period for text messaging. Text messages can be composed without handwriting. Text messages are short, ranging from a single word to one or two dozen words. And text messages are a real activity rather than a mere school exercise.

And there is one additional spectacularly great feature: text messages are a great way for small children to engage positively with the digital age.

The internet is amazing. It is a global many-to-many information platform. I think it is probably the greatest invention of all time. Even if you don’t buy that, I say with confidence that it has been an enormous enabler for my life, having grown up along with it as a nerdy school-aged kid in the early 90s. For me it has been a platform for meeting prospective colleagues and future great friends, for learning about anything and everything, for getting an audience for my writing, for engaging in a great collective software project, for finding niche communities, for doing day-to-day coordination with infrastructure that was almost unimaginable two generations ago, and for much else.

I want my children to have a similarly positive experience with the internet. The digital world is a major slice of Alice’s present and future world. But, unfortunately, when young children go online, it tends to take the form of passively consuming overstimulating slop. Partly for this reason, there is a widespread and understandable allergy to “screen time” in early childhood.

But “screen time” is a confused concept. It groups together very different things, such as FaceTiming with a grandparent and passive digital overstimulation. The term makes it hard to see that Alice learning to text “I love you” to her mother has nothing in common developmentally with e.g. braindead Cocomelon YouTube shorts.

The trepidation that parents feel about overdosing on the latter should not be extended, not even a little bit, to the former. Were it not for that trepidation, the sort of thing I’m doing with Alice would be common. If you’re not blocked from thinking it’s good, and if you understand Montessori’s writing-before-reading approach, it’s a braindead obvious thing to at least try. It’s 20-year-old technology and a 120-year-old pedagogy.

Alice sending and receiving text messages is an unadulterated win with respect to her burgeoning literacy, her relationships with her family and friends—and also to her relationship with technology. It’s the perfect concrete introduction to the world of globally transmitted bits. She gets to do something with it, something she couldn’t do otherwise, in a way that builds her competence, confidence, and understanding of how it works and what it means for her.

Montessori herself was a great proponent of technology. She thought it critically important to educate and positively celebrate industrial advances with children. Digital technology was before her time, but there is evidence that she was interested in classroom media.4 Moreover, Montessori was a great proponent of having children participate in real life, including the (for her new) world of machines and commercialized electrification.

To be clear: I don’t want to presume or even speculate on what Montessori herself would think of my iPad experiment with Alice, or of the digital world more broadly. And getting this sort of technology into a Montessori classroom, as opposed to a home, would be a complex matter, involving a type of ongoing collaboration between technologists and Montessori early childhood educators that I don’t think exists today.

But I, at least, am exceedingly pleased with how the experiment has turned out for my daughter. It matters a great deal to me that Alice can read and write, that she comes to love writing to her intimates, and that she is a masterful agent, not a helpless victim, when it comes to the world of bits.

Have a great weekend,

Matt Bateman

Board of Directors, Higher Ground Education

Photography is under-explored as a skill that trains one to look, to see, in analogous (but different) ways as sensorial exercises in Montessori train such capacities.

We also periodically stepped back in to tweak the iPad configuration. These three affordances (camera, writing, texting) remained constant, and no others were added, but we changed how they were arrayed, tweaked the availability of spellcheck and audio input (currently both are off), etc.

An analogy: all the practical life exercises are valuable, but it is additionally ennobling when a practical life exercise fills a real need (e.g. peeling an orange to eat the orange).

Mark Powell writes, citing Tim Seldin and a 1932 Italian magazine article edited by Montessori: “Especially while in India, Dr. Montessori was fascinated by 16mm films that showed news, cities, natural phenomena, mechanical or scientific apparatus, or attempted to portray history. She supposedly imagined a day when elementary children could load and view film themselves from a library of images and sound.”

This makes me so happy! I’m excited for when my daughter gets older and can start expressing herself with words.

This is gold! I’m going to look into setting up messaging on the kid laptop. Maybe they can chat with their cousins!